Legal custody arrangements are different in every province and state, but there are some similarities. Here’s a brief summary of who often gets custody of the children after divorce and how the “best interests of the child” affect a judge’s decision.

This is part of a paper I wrote for one of my social work classes (I’m working on my Master’s of Social Work at the University of British Columbia). The paper was called Equal Parenting Presumption: An Exploration of the Possibilities, and it was for a class on Social Justice and Children’s Rights.

It’s a fascinating topic – especially if you aren’t a divorcing couple who is concerned about who gets custody of children after divorce! If you are getting divorced, custody arrangement can be brutal. Emotionally, psychologically, and financially, custody arranges are often the bane of a couple’s existence.

Custody Arrangements After Divorce

Most separating and divorcing couples do not go to court to make custody arrangements. Even when a court case is started, most family cases settle before they reach trial. Many divorcing parents come to an agreement on their own, often with the help of lawyers or through mediation.

If a couple can’t agree on custody arrangements, they can go to court and ask a judge to settle issues such as parenting arrangements, child support, spousal support, and how to divide property and debt. The judge makes orders, and the couple must follow the decisions rendered by the court. Some circumstances are more complicated than others, such as in the case of family violence, mental or emotional health issues, and protection orders.

Under the Divorce Act in British Columbia, a judge makes decisions about custody based on the “best interests of the child.” Theoretically, a judge will consider the conditions, means, needs and other circumstances of the child and family, and decide what would best protect the child’s physical, psychological, and emotional safety, security, and well-being.

A potential problem with this theory is that “best interests of the child” is difficult to put into practice. That is, it is possible that a judge’s idiosyncrasies, values, and beliefs will decrease his or her objectivity, and lead to a biased decision that might have unintentionally disastrous effects on the family as a whole. The best interests of the child may not be best served by a judge in a contested custody hearing.

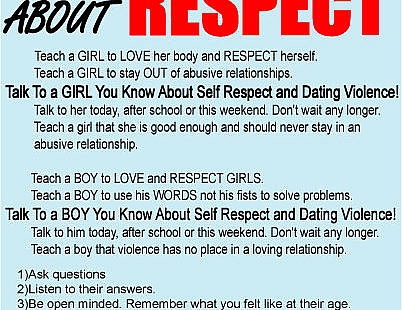

For parents and/or courts trying to come to an agreement about custody, the best interests of the children should be their primary consideration. However, problems arise when one parent use their children to hurt the other parent. There are many, many cases of devastating child custody battles that are inflamed by lawyers, courts, and even judges. Further, what one party believes to be best for a child may not be what another party thinks is best.

If you haven’t decided to get divorced yet, read The Top Predictor of Divorce – and How to Avoid It.

The Effects of Sole Custody Arrangements

Sole custody is associated with diminished parent-child relationships and can lead to the absence of a parent from a child’s life (Kruk, 2012). This increases conflict between parents, and can even lead to incidents of first-time family violence in some cases. Children in particular are negatively affected by these effects, in the form of disrupted parent-child relationships, emotional insecurity, compromised mental and emotional well-being, and increased conflict between parents that compromises a child’s physical security and well-being.

Despite the problems associated with sole custody for both children and parents, it is the default position of the Divorce Act.

Parental Alienation Syndrome After Divorce

Parental alienation syndrome (PAS) is a disorder that arises primarily in the context of child-custody disputes. Children begin a campaign of denigration without justification against a parent. PAS results from the combination of a programming or alienating parent’s indoctrination (or “brainwashing”), and the child’s own contributions to the vilification of the targeted parent. This is different from true parental abuse and/or neglect. Gardner (1992) posited that child sexual abuse allegations were rampant in custody litigation, and that 90% of children in custody litigation are suffering from PAS.

The alienating parent has specific reasons or an agenda for turning a child against the other parent. It may help to counterbalance the alienating parent’s feelings of inadequacy, lack of self-worth, powerlessness, or merely being overwhelmed with the future prospect of facing judicial proceedings. Turning a child against a parent may have its basis in revenge, guilt, fear of loss of the child, desire to have full control over the child, jealousy of the other parent, the desire to for increased child support or alimony. There may also be a personal past history of abandonment, alienation, physical or sexual abuse, self-protection, or even the loss of one’s identity.

There are many detractors of Parental Alienation Syndrome, citing its circularity, conclusory reasoning, and lack of empirical basis (Meier, 2009). Despite this, PAS has for over a decade been ubiquitous in family courts and plays a significant role in custody litigation. It is routinely invoked whenever any kind of possible abuse is raised and/or a mother seeks to restrict a father’s visitation when custody arrangements favor the mother. PAS is very complicated, and even though it is not scientifically proven, it is often used to disrupt custody arrangements – most often the father’s. It is most often the mothers who unconsciously and subtly undermine their children’s relationship with their fathers (who are most often the noncustodial parents). PAS may be a significant and negative influence on parent-child relationships – and it may be perpetuated by the current Divorce Act.

Bill C-422 – Shared Presumption of Parenting

Bill C-422 was an enactment intending to amend the Divorce Act and replace the concept of “custody orders” with that of “parenting orders.” It would instruct judges, when making a parenting order, to apply the principle of equal parenting unless it is established that the best interests of the child would be substantially enhanced by allocating parental responsibility other than equally. This may help all family members transition from marriage to divorce.

This bill was not passed. According to the Canadian Bar Association (2010), if passed Bill C-422 would have changed the primary focus in custody and access matters from what is best for children to equal parental rights. Parenting is about putting children’s best interests first – not about adults claiming rights and demanding to get custody of children after divorce. Thus, according to the Canadian Bar Association (2010), this bill would take the focus away from children in favour of parental rights, detract from individual justice, and promote further and more contentious litigation.

It seems there are two sides to the debate of how custody should be decided after divorce. The current system favors the judge deciding what is in the “best interests of the child.” A new system is being debated, in which there is an automatic legal presumption of equal shared parenting – which is the crux of Bill C-422.

What are your thoughts on who gets custody of the children after divorce? Feel free to share below.

Is this your first holiday season after getting divorce and making custody arrangements? Read Surviving Your First Christmas After Divorce.